Can Cursor AI Read Jupyter Notebook Cells?

The Joy of Using Jupyter Notebooks with Cursor AI

I now use Jupyter Notebooks in Cursor AI. Can you imagine the relief? I just love that slick RED and GREEN style of AI programming recommendations pouring down over your code like paint! To have that radically enabling exploratory environment of a Notebook simultaneously with the radically enabling assistive power of an AI… well, it’s radially enabling!

Me: Why hello there, Claude! Nice to see you here in my Jupyter Notebook. Can you see my cell 1?

Claude 3.7 Sonnet: <think> I can see that the user is working with a Jupyter Notebook file named “Untitled.ipynb” in a path that appears to be “pipulate/client/test/”.

The notebook content shown has:

- One input cell labeled as “in[0]” with the simple code

print("Hello World!") - It looks like the user has not executed the cell yet (otherwise it would typically show output)

The user is asking if I can see their “cell 1”. In Jupyter Notebook terminology, cells are typically numbered starting from 0, so what they’re showing me is actually cell 0 (labeled as “in[0]”). I only see one cell in the provided content, so I should clarify this in my response. </think>

Hello! Yes, I can see your Jupyter Notebook “Untitled.ipynb”. I can see cell 0 (labeled as in[0]) which contains:

print("Hello World!")

However, I don’t see a cell 1 in the content you’ve shared. The notebook excerpt you provided only shows a single cell (cell 0) with the “Hello World!” print statement. Is there something specific you’d like help with regarding your notebook?

Cursor AI Can’t See Notebook Cell Output

Me: Nice! That’s a yes. There is no real numbering in the Jupyter UI. That number between the square brackets you’re referring to is the number of times the cell was executed. So if I ran that “hello world” cell twice and:

Save And Export Notebook as / Executable Script, it would turn out as:

…the resulting Untitled.ipynb would read:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# In[2]:

print("Hello World!")

# In[ ]:

Understanding Jupyter Cell Execution Counts

…which is not really fixed index cell numbering at all. I’m surprised you don’t know that, Claude. I guess people don’t really talk about that kind of stuff much in the material used to train you.

Testing Claude’s Ability to Parse Jupyter Notebooks

Anyway, I’m really interested in what you see in context here, especially if you

see a distinction between the cells. Do you see this Unititled.ipynb like that

Python code I just shared, or in some other way? You’re not limited to just

seeing the first cell, are you? Here, let me put a secret word in the second

cell. What’s the secret word?

Claude Doesn’t Understand .ipynb [1] Execution Count Brackets

If you’re not familiar with my tech journal style yet, usually the whole article thus-far becomes the next prompt, or at least a large enough chunk of it to keep the conversation going, drilling-down on whatever it is I’m trying to discover – in this case, how Cursor AI sees Notebooks.

Claude: <think> I made a mistake in my interpretation of Jupyter Notebook cells. You’re absolutely right about how Jupyter Notebooks work:

- The number in

In[n]represents the execution count (how many times cells have been executed in the session), not a fixed cell index - Empty brackets

In[ ]indicate a cell that hasn’t been executed yet - When exporting a notebook, these execution counts are preserved in the comments

Looking at your original file again:

in[0]: print("Hello World!")

in[1]: # flibbertigibbet

I can now see this shows two cells:

- First cell with execution count 0:

print("Hello World!") - Second cell with execution count 1:

# flibbertigibbet

The second cell contains just a comment with the word “flibbertigibbet”, which appears to be the secret word you’re asking about.

I should acknowledge my error and confirm that I can indeed see both cells, including the second cell with the secret word. </think>

You’re absolutely right, and I appreciate the correction! The numbers in the brackets (In[n]) represent execution counts (how many times cells have been executed during a session), not fixed cell indices as I incorrectly stated. That’s an important distinction about Jupyter Notebooks that I should have recognized.

Looking at your original notebook excerpt again, I can now see that there are indeed two cells:

- A cell with execution count 0:

print("Hello World!") - A cell with execution count 1:

# flibbertigibbet

So to answer your question, the secret word you placed in the second cell is “flibbertigibbet”.

I can see both cells in the context you provided, and I appreciate you testing my ability to properly parse the notebook format!

Testing Live File Updates Between JupyterLab and Cursor

If you’re using Notebooks in Cursor AI, chances are you have a copy of JupyterLab or transitional Jupyter Notebooks running somewhere else on your machine, because these VSCode-forks have to get the running kernel from somewhere. This is an experiment to see how soon Claude can “see” stuff after a file-save over on the JupyterLab side.

Me: That’s a big ol’ confirmation. I didn’t even do that typing in Cursor

AI. I actually did that over in JupyterLab in the browser and saved it, coming

back to Cursor and seeing it dynamically live-loaded back in! And

Untitled.ipynb was selected in-context when I asked you that question, so you

must have read if off the drive. Nice!

I just made the 3rd cell. Can you tell me anything about that?

Claude: <think> Let me look at the provided context again:

in[0]: print("Hello World!")

in[1]: # flibbertigibbet

in[2]: # Thingamajig

Yes, I can see that there’s now a third cell with execution count 2 that contains the comment “# Thingamajig”. This suggests that the file was updated with a new cell since the previous message, and I’m now seeing this updated version because the file was selected in-context when the user asked the question. </think>

Yes! I can see the third cell you’ve added to your notebook. It has an execution count of 2 (in[2]) and contains the comment:

# Thingamajig

This confirms that I’m able to see the updated content of your Untitled.ipynb file as you modify it externally in JupyterLab and then return to Cursor. It seems the file context is being refreshed, allowing me to access the current state of your notebook file when you ask questions about it. That’s quite useful for providing help with notebooks you’re actively working on!

Examining Differences Between Jupyter Notebook Cells

Can Claude in Cursor AI distinguish between a Jupyter Markdown cell and a code execution cell? Their representation in the downloadable executable

.pyscripts are very similar. The pattern is hash space hash (##) indicating markdown. I have to coerce Claude into realizing.

Me: Exactly! But do you see anything special about the line containing flibbertigibbet and the line containing Thingamajig? Given what you know about Jupyter Notebooks, are there any inferences you might be able to make about what makes them different, aside from the words themselves?

Claude: <think> Let me carefully examine the two cells:

Cell 1 (execution count 1): # flibbertigibbet

Cell 2 (execution count 2): # Thingamajig

Both cells start with the # character, which in Python indicates a comment. This means neither cell is executing any actual Python code - they’re just comment lines.

The main differences I can see:

- Different execution counts (1 vs 2)

- Different comment text (“flibbertigibbet” vs “Thingamajig”)

- Capitalization difference - “flibbertigibbet” starts with lowercase, while “Thingamajig” starts with uppercase

In Jupyter Notebooks, comments alone don’t produce any visible output when executed. They’re simply annotations.

One possible inference is that in the original notebook view, these might appear differently if there were any outputs associated with these cells (which wouldn’t be expected for comment-only cells, but it’s possible you executed them and they have some execution metadata).

Also, it appears that Cell 2 (Thingamajig) might have additional whitespace after it as there seem to be blank lines after it in the file representation.

I’m not seeing any other significant differences based solely on the representation in the file. </think>

Looking at both cells more carefully:

Cell 1 (execution count 1): # flibbertigibbet

Cell 2 (execution count 2): # Thingamajig

The main difference I notice is that after the “Thingamajig” cell, there appear to be additional empty lines in the notebook. In Jupyter notebooks, these empty lines after a cell can indicate:

- There might be another cell that hasn’t been executed yet (which would show as

In[ ]) - Or simply that you’ve added some spacing after that cell

Another inference is that both cells contain only comments (they start with #), so they wouldn’t produce any output when executed. However, they still increment the execution counter when run, which suggests you’ve executed both of these comment cells despite them not producing visible output.

Is there another distinction between these cells that you’re thinking of?

Claude Will Make Up Stories About Code Execution Order

If Claude is seeing Jupyter Notebooks how the

.py-files look when downloaded, there’s no way it knows your code execution order. It has enough information to infer execution-counts. But the order? No way.

Me: That is totally incorrect to the point of hallucinating. First of all, I

haven’t executed any of the cells other than the first one which I executed

twice. Second of all, when I Save And Export Notebook as / Executable

Script, the resulting code looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# In[2]:

print("Hello World!")

# In[ ]:

# flibbertigibbet

# # Thingamajig

# In[ ]:

…which I’m assuming is a lot like what you’re able to see when I put

Untitled.ipynb in prompt context. And so, my question to you is looking at the

characters that immediately precede each word, can you tell anything special

about one versus the other? And given what you know of Jupyter Notebooks, can

you tell me what you think that might mean?

Claude: <think> Looking at the full notebook export that you’ve shared, let me carefully examine the formatting:

#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# In[2]:

print("Hello World!")

# In[ ]:

# flibbertigibbet

# # Thingamajig

# In[ ]:

Now I see what you’re highlighting. The key difference is:

- For “flibbertigibbet”: It’s preceded by a single

#character (# flibbertigibbet) - For “Thingamajig”: It’s preceded by two

#characters (# # Thingamajig)

This is a significant difference in Jupyter notebooks. When a line starts with # it’s a regular Python comment. But when a line starts with # # (or multiple #s), it’s actually a Markdown cell in Jupyter, not a Python code cell.

So “flibbertigibbet” is in a Python code cell as a comment, while “Thingamajig” is in a Markdown cell. That’s why they would look different when rendered in the notebook interface - the Markdown cell would format “Thingamajig” as a heading (since it has a # at the beginning of the Markdown content).

This is an important distinction in Jupyter notebooks - code cells vs. Markdown cells. The export format shows this by putting an extra # before Markdown content.

</think>

You’re absolutely right, and I apologize for my incorrect interpretation. Looking at the exported script you shared, I can now see the critical difference:

- “flibbertigibbet” is preceded by a single

#:# flibbertigibbet - “Thingamajig” is preceded by

# #:# # Thingamajig

This indicates that “flibbertigibbet” is in a regular Python code cell (with the # making it a comment within that code cell), while “Thingamajig” is in a Markdown cell (where the first # is Jupyter’s way of indicating Markdown content in the exported script, and the second # would make it a heading in Markdown).

In Jupyter, this distinction means:

- The “flibbertigibbet” cell would execute as Python (though doing nothing since it’s commented)

- The “Thingamajig” cell would render as a Markdown heading when displayed in the notebook

Thank you for pointing out this distinction - it’s an important aspect of Jupyter notebooks that I should have recognized from the file format.

You Don’t Know Notebooks, Claude

As popular as our beloved Notebooks are, they’re not what AIs have been trained on.

.ipynb-files are dirty, dirty JSON jumbles. You can bet they were curated out of the training data. And if the.pythat lurks beneath was extracted, it’s just going to look like Python within[x]comments.

While these LLMs have been trained on coding, and even by now know quite a bit about the types of coding environments Curser AI and Windsurf use, they know very little about actual Notebooks, and their strange REPL code-execution context.

But it does appear that they see a text-file representation somewhat similar to

the export of the .py-file. The alternative of them getting the whole .ipynb

file would be confusing to them resulting in a useless experience for the user.

So it’s probably nbconvert or something like it there in the process.

Okay, one more test. I need to see if they can see the output cell. This is a bit of a trick because anything I put in the workspace is readable by Cursor AI, given VSCode Workspace contexts.

Testing Claude’s Ability to See Jupyter Cell Output

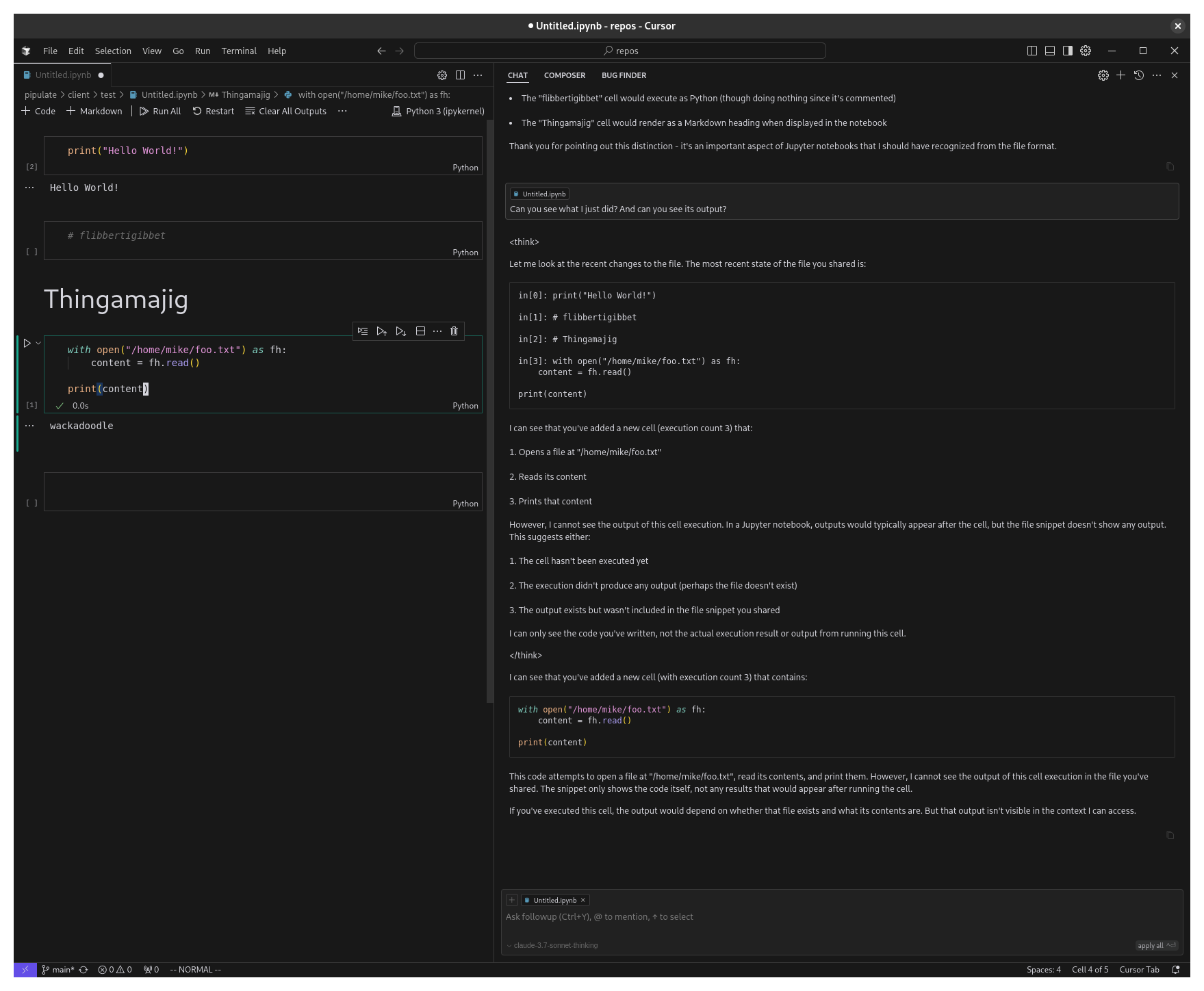

Me: Can you see what I just did? And can you see its output?

And now the moment you all came reading for. Can Claude see your Jupyter Notebook cell output in Cursor AI? No. It’s just like the Terminal in that regard. Can you imagine the privacy violation faux pas that would mean? Both for Terminal and Notebook cell output. Same issue. They’re being conservative first, respecting privacy. Yes, this cuts of Agentic Kung Fu, but that will come in time, the way async under Notebooks did with

nest_asyncio.

Claude: <think> Let me look at the recent changes to the file. The most recent state of the file you shared is:

in[0]: print("Hello World!")

in[1]: # flibbertigibbet

in[2]: # Thingamajig

in[3]: with open("/home/mike/foo.txt") as fh:

content = fh.read()

print(content)

I can see that you’ve added a new cell (execution count 3) that:

- Opens a file at “/home/mike/foo.txt”

- Reads its content

- Prints that content

However, I cannot see the output of this cell execution. In a Jupyter notebook, outputs would typically appear after the cell, but the file snippet doesn’t show any output. This suggests either:

- The cell hasn’t been executed yet

- The execution didn’t produce any output (perhaps the file doesn’t exist)

- The output exists but wasn’t included in the file snippet you shared

I can only see the code you’ve written, not the actual execution result or output from running this cell. </think>

I can see that you’ve added a new cell (with execution count 3) that contains:

with open("/home/mike/foo.txt") as fh:

content = fh.read()

print(content)

This code attempts to open a file at “/home/mike/foo.txt”, read its contents, and print them. However, I cannot see the output of this cell execution in the file you’ve shared. The snippet only shows the code itself, not any results that would appear after running the cell.

If you’ve executed this cell, the output would depend on whether that file exists and what its contents are. But that output isn’t visible in the context I can access.

Discovering Cursor AI’s Limitations with Jupyter Cell Output

It appears that Cursor AI cannot read the output of Jupyter Cells even if

executed. This is a fascinating and important point, with ramifications from

privacy assurances to rapid feedback-loop limitations. To double check this

finding, I re-executed the cell from within Cursor AI and saved the resulting

.ipynb to make the output into the Notebook JSON metadata, and asked Claude

again if it could see the output and it still couldn’t. I’m fairly certain

Notebook cell output is not in the AI prompt context.

Let’s double-check with Perplexity.

First-hand knowledge is best. Learn through testing directly. While sure someone may have answered it on the net, and it got into the search results or the training data, are you really gonna trust that? I don’t, but I still can’t resist checking what the answer would be.

Me: Can Cursor AI read the output of Jupyter Notebook cells?

Perplexity: Cursor AI has limited ability to directly read and interpret the output of Jupyter Notebook cells. Here are the key points based on the provided information:

- Direct Output Reading:

- Cursor AI does not inherently include cell outputs as part of its context when working with Jupyter Notebooks. This means it primarily relies on the code written in the cells rather than their execution results[4][5].

- There have been feature requests to include cell outputs in the AI’s context for better suggestions and analysis, but this functionality is not yet standard[5].

- Workarounds:

- Users can manually provide outputs to Cursor by printing results or taking screenshots (for visualizations) and uploading them into Cursor’s interface. This allows the AI to analyze and generate insights based on the shared outputs[1].

- For API responses or similar outputs, users can print them to a cell, and Cursor can then process these outputs if explicitly shared[8].

- Privacy Concerns:

- Since cell outputs may contain sensitive data, there is ongoing discussion about making output inclusion an opt-in feature to address privacy concerns[3][4].

In summary, while Cursor AI can assist with code and provide insights, its ability to directly utilize Jupyter Notebook cell outputs is limited and requires manual intervention or workarounds.

Citations:

[1] https://www.reddit.com/r/cursor/comments/1jdatdg/cursor_ide_for_jupyter_notebooks_data_science_and/

[2] https://mikelev.in/futureproof/jupyter-notebook-vscode-cursor/

[3] https://forum.cursor.com/t/data-protection-when-working-with-jupyter-notebooks/13306

[4] https://forum.cursor.com/t/cursor-tab-read-notebook-output/16664

[5] https://forum.cursor.com/t/support-notebook-cell-output-inclusion-in-context/28876

[6] https://forum.cursor.com/t/jupyter-notebooks-in-cursor-yes-please/22015

[7] https://github.com/getcursor/cursor/issues/576

[8] https://forum.cursor.com/t/is-cursor-aware-of-api-responses/2942

What You All Want: Agentic Loops In Notebooks

Yeah, yeah, I get it. That stuff you see in Goose AI, Cline and Manus. You want it in your Notebook and you want it NOW! Maybe it’s possible. Let’s do some Deep Research!

The Perfect Marriage of Notebooks and Agentic Systems

We are in the verge of that same strange feedback loop we see in self-prompting agentic systems, but in the exploratory environment of a Jupyter Notebook. That’s going to be cool! It’s a match made in heaven.

Understanding Modern Agentic AI Capabilities

It’s not too far off from what Goose AI, Manus and Cline which are all agentic, chain-of-thought reasoning, plan/act mode, auto-debugging, recursive self-improvement, autonomous tool invocation, memory-based task continuity, modular task execution, context-aware decision-making… whatever the heck you want to call taking the output and feeding it back into the input.

The Challenge of Controlling Agentic Processes

But you don’t want the agentic things running away from you. They’re not going to make it to the end of the process perfectly most of the time. But re-running them from the beginning of the chore and hoping they take all those same steps… ugh! It screams Notebooks.

Safety First: Sandboxing and Control Mechanisms

Taking the output of one process and feeding it into the input of another, and giving individual steps the ability to tool-call with protocols like MCP (model context protocol) is pretty scary and all the live versions are heavily sandboxed so they can’t fubar your machine. Aside from this sandboxing, the modest first step is wrangling this potentially runaway self-prompting beast is getting them to love doing their Agentic work inside a Notebook environment.

The Vision: Interactive AI Development in Notebooks

Can you imagine Markdown documenting as you go, having that mid-execution frozen state of a Notebook but with Agentic process interrupted and frozen awaiting your fine-tuning directional prompts? Yeah, I get why you want Claude to be able to see your Notebook cell output. Let me assure you, you are not alone.

So, I’ll do some research beyond a quick Perplexity ping to see what else is out there.

Let The Research Begin: How Can Cursor AI See Notebook Cell Output

I focus on visibility of Jupyter Notebook cells to speed up the simple manual copy/paste feedback loop. The whole actual agentic solution inside a Notebook I think is deserving of a separate article in the future.

Me: Hey ChatGPT 4.5 Deep Research, what are the techniques people are using today to make the cell output of a Jupyter Notebook in Cursor AI visible to the code assistant for more rapid feedback loops?

ChatGPT 4.5: Could you please clarify whether you’re looking for officially supported techniques from Cursor AI, or also community-driven workarounds and plugins? And are you specifically focused on making outputs visible for code assistants within Cursor, or would you like comparisons with other AI-enabled IDEs like Copilot or CodeWhisperer as well?

Me: Right now, just in Cursor. And start with the official and if the results are less than satisfying, fall over to the community-driven workarounds and plugins.

ChatGPT 4.5: Got it. I’ll dig into how people are currently enabling Jupyter Notebook cell outputs to be visible to the code assistant in Cursor AI—starting with official methods and then falling back to community-driven workarounds, plugins, or hacks if needed.

I’ll report back soon with what I find.

Integrating Jupyter Notebook Outputs into Cursor AI’s Assistant Context

Official Support (or Lack Thereof) for Notebook Output in Cursor AI

Currently, Cursor’s AI code assistant does not natively include Jupyter Notebook cell outputs in its context. In practice this means the assistant “ignores” the printed results, figures, or errors from code cells unless the user explicitly shares them. Multiple users have raised this limitation: “It feels as if the notebook outputs are not taken into context for anything” (Jupyter notebook output not taken into context · Issue #2746 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub). The importance of output context is well recognized – one feature request notes “the output of the cells is a very important piece of context for any Cursor feature” (Support notebook cell output inclusion in context - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) – but as of early 2025, there is no official feature to feed cell outputs into the AI’s prompt automatically.

Why no built-in support yet? Two main reasons emerge from official discussions. First, including outputs (which might contain sensitive data like dataset values, API responses, etc.) poses privacy concerns if sent to the model. A team member suggested that if output-context were added, it should be opt-in due to privacy (Support notebook cell output inclusion in context - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum). Second, technical constraints like context length: large outputs (e.g. a big

df.head()or Plotly chart) could overflow prompt limits. In fact, users observed that when forcing a whole notebook into chat, Cursor would truncate lengthy outputs to avoid huge prompts (New release completely broke jupyter notebook functionality in cursor chat - Bug Reports - Cursor - Community Forum). (In one update, inline image outputs started getting included fully, causing “long file” warnings and token bloat (New release completely broke jupyter notebook functionality in cursor chat - Bug Reports - Cursor - Community Forum).) In short, official documentation currently offers no automatic output-sharing, focusing only on code and markdown content. The Cursor team is aware of the demand – a staff member noted “there seems to be a lot of demand… I can bring up internally what features people want most in notebooks” (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) – and many users specifically emphasize that “being able to use cell output as context would be a step change in productivity” (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum). However, until the developers implement such a feature, users must rely on manual or community-driven solutions.

Community Workarounds to Expose Execution Outputs to the AI

In the absence of native support, Cursor’s user community has devised various workarounds to incorporate cell outputs into the assistant’s context. These techniques, while not as seamless as a built-in feature, can help the AI “see” your results for tighter feedback loops:

-

Manual Copy-Paste of Outputs: The most straightforward solution is simply copying important outputs (e.g. error tracebacks, DataFrame previews, computed values) and pasting them into the conversation or into a markdown cell. This ensures the assistant can analyze them. Many Cursor users resort to this today – for example, one GitHub issue confirms “Now I am manually copy[ing] the output, which is a little bit frustrating.” (Jupyter notebook output not taken into context · Issue #2746 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub). By pasting an output (or a summary of it) into the chat, you make it part of the prompt so the AI can incorporate that information in its next suggestion. This is tedious but effective for things like debugging (pasting stack traces) or data analysis (pasting a few lines of a computation result).

-

Printing or Saving Outputs to a File: A clever hack is to redirect outputs to a file that Cursor can read. Instead of relying on the ephemeral notebook output area, you can have your code write results to a

.txtor markdown file in the workspace. For instance, one user working with an API had the idea to “write the response toresponse.txtand then reference that file” (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum). Cursor’s assistant can then be prompted to open or consider that file’s contents. Because the file is part of your project, the assistant can retrieve its text as context (provided it’s not too large) just like any source code. This workaround essentially turns runtime output into a static text that the AI will treat as just another piece of project data. Community members confirm this approach “could also work” (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum) for making the AI aware of dynamic results without manual copy-paste each time. Similarly, you could save a DataFrame’s summary to a CSV or markdown table that the assistant can then read and reason about. -

Leverage Notebook Outputs via Chat Context (Limited): Some users have experimented with indirectly including outputs by using Cursor’s chat on the notebook file. For example, one forum tip suggested that if you print the result in a Jupyter cell, you can then ask the assistant about it, since “Cursor can read the cell outputs and answer questions with that context.” (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum) In practice this method is hit-or-miss. It appears Cursor’s chat may ingest the notebook’s JSON (including output text) when you use certain commands (like inserting the file into chat), but it isn’t reliable or complete. As noted, earlier versions would drop large outputs (only partial output from a

df.head()might appear) (New release completely broke jupyter notebook functionality in cursor chat - Bug Reports - Cursor - Community Forum). So while you can try to print concise outputs (say, a small dict or short string) and then use the Chat mode on that notebook, be aware the AI might still not “see” everything. Essentially, this trick isn’t officially supported – it’s more of an accidental capability when using the “whole file to chat” feature. Small text outputs could get through, but anything lengthy or non-text (images/plots) likely won’t. Use this with caution: it can save a step for small results (avoiding manual copy) but double-check that the assistant actually received the info (you might ask it to echo back what it saw from the output to be sure). -

Utilizing the Integrated Terminal for Outputs: An alternate approach is to sidestep the notebook UI for execution and use a .py script or Cursor’s terminal to run code, then feed the output to the AI. Cursor’s “Auto Debug” features work in the terminal context – for example, if you run tests or scripts in the terminal panel and get an error, Cursor can capture that and offer a fix. (This is something users have and want more of – a request exists to “auto… add to chat context a Jupyter notebook cell output, similar to what’s available within the terminal” (terminal support for Jupyter notebook cell outputs · Issue #1000 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub), implying the terminal already had some auto-context injection for its outputs.) So, one strategy is: during development, run code in a script (or use VS Code’s Python Interactive mode

#%%in a .py file) so that output appears in a text form (terminal or output pane). Then, either let Cursor’s agent auto-include it if supported, or copy it from there. A few advanced users even configure their workflow such that they don’t let Cursor modify the.ipynbdirectly – instead, they test code in.pyfiles or the terminal, where the AI’s context handling is better, and only later assemble the confirmed code into a notebook. This prevents the AI from getting “confused” by hidden state in notebooks and gives you explicit control over what output to share (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum). It’s a bit of a roundabout hack, but it streamlines the feedback loop by using Cursor in an environment where it can see outputs (e.g. error logs in terminal) and then manually merging results back into the notebook. -

Community Extensions or Patches: As of now there isn’t an official plugin solely for syncing outputs to Cursor’s context, but the community has shown willingness to patch Cursor’s Jupyter support in other ways. For example, early adopters solved notebook-run issues by replacing Cursor’s bundled Jupyter extension with the official VS Code Jupyter extension ([Solved] Jupyter Notebook Support · Issue #576 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub). This hack made notebooks usable in Cursor and ensured “the AI kn[ows] what [you are] writing in each block” ([Solved] Jupyter Notebook Support · Issue #576 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub) (i.e. the assistant sees the code cells). While this fix didn’t magically include outputs, it improved overall Jupyter functionality and demonstrated how power users tweak Cursor under the hood. Similarly, one could imagine a custom script or extension that on each cell execution, takes the output and inserts it into a hidden markdown cell or a sidecar text file for the AI – though no public tool has been published yet. For now, most people rely on the simpler manual methods above.

Looking Ahead: Ongoing Discussions and Expectations

The demand for true integration of Jupyter outputs into Cursor AI is loud and clear across forums and GitHub. Dozens of users have upvoted requests to “support notebook cell output inclusion in context” (Support notebook cell output inclusion in context - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) and to improve the notebook editing experience in general. Cursor’s team has acknowledged these requests and is reportedly prioritizing notebook support enhancements. We can likely expect future updates to address this, potentially by allowing opt-in inclusion of outputs. For example, the assistant might in the future offer a toggle or command to grab the latest cell output into the chat (with warnings about data sensitivity). Until then, the community’s stopgap solutions – copying outputs, saving them to files, and creatively structuring one’s workflow – are the way to go for faster feedback loops.

In summary, Cursor AI currently doesn’t automatically “see” Jupyter cell outputs, but resourceful users are bridging that gap themselves. By manually feeding important result data back into the prompt (or via intermediate files), you can give the AI the context it needs to provide informed suggestions (Jupyter notebook output not taken into context · Issue #2746 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub) (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum). It’s not a perfect solution, but it empowers you to still leverage Cursor’s AI on notebook-based projects. And with the strong community pressure and active discussion on Cursor’s forums, there’s good reason to hope that a more elegant, official solution (perhaps a Notebook-Output-to-Context feature) will be implemented in the near future.

Sources

- Cursor Community Forum – “Support notebook cell output inclusion in context” (feature request) (Support notebook cell output inclusion in context - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) (Support notebook cell output inclusion in context - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum)

- Cursor Community Forum – “Jupyter Notebook support” (user discussion; multiple posts about missing output context) (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum) (Jupyter Notebook support - Page 3 - Feature Requests - Cursor - Community Forum)

- GitHub Issue – Jupyter notebook output not taken into context (#2746, Feb 2025) (Jupyter notebook output not taken into context · Issue #2746 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub) (Jupyter notebook output not taken into context · Issue #2746 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub)

- Cursor Community Forum – “Is Cursor aware of API responses?” (discussion of printing output vs. writing to file) (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum) (Is Cursor aware of API responses? - Discussion - Cursor - Community Forum)

- Cursor Community Forum – Bug report about notebook outputs in chat context (Aug 2024) (New release completely broke jupyter notebook functionality in cursor chat - Bug Reports - Cursor - Community Forum)

- GitHub Issue – Feature request to add notebook output to chat context (#1000, Oct 2023) (terminal support for Jupyter notebook cell outputs · Issue #1000 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub)

- GitHub Issue – “[Solved] Jupyter Notebook Support” (#576, May 2023) – community patch for VSCode Jupyter extension ([Solved] Jupyter Notebook Support · Issue #576 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub) ([Solved] Jupyter Notebook Support · Issue #576 · getcursor/cursor · GitHub).

Exploring Marimo as a Jupyter Alternative

Wow, okay that was quite a journey. Copy/paste then it is for awhile. But that was a worthy exploration. Also, I became aware of Marimo, an new kind of reactive Notebook and competitor to Jupyter. Here’s the Marimo video and the FAQ. Wow, gotta learn more about that, and there is much that sounds like Pipulate, but it suggest packaging it up with Docker for distribution.

Comparing Marimo to Traditional Notebooks

Marimo could end up being an alternative platform distributed with a Pipulate workflow. Marimo talks about Jupyter Notebooks as web apps, but it’s still exposed Python and all. Their definition of a web app is still actually still a notebook. And so it doesn’t’ really do away with the intimidation factor for non-programmers. It’s for the same audience as Notebooks themselves, and not for a new non-technical user like canned Pipulate workflows.

Integrating Marimo into the Development Stack

But it still takes development to can Pipualte workflows, and so Marimo can be

side-by-side complementary and an alternative to JupyterLab. I could put it on

its own start and stop like I do JupyterLab to run locally from within the

same Nix Flake as Pipulate. I basically package Pipulate up with its own Python

webdev environments. You know, I could throw in one of the still

free-as-in-libre VSCode forks like [VSCodium)(https://vscodium.com/) and make it

a really equal opportunity editing environment.

The Challenges of Vim Mode in Notebooks

And finally as an added in bonus because I really doubt I’ll make a separate

article on it, vim mode in a Notebook is really awkward, be it in Cursor AI or

a regular web-based JupyterLab Notebook environment. OMG, the mixed contexts. As

much of a vim-head as I am, cells an vim keystrokes don’t live together

harmoniously. I mean, what’s Esc even mean? Nested context modes of Notebook

cells and vim editing? No thank you!

Managing Vim Mode in Modern IDEs

But now I have to learn how to toggle vim-mode on and off quickly. Finally, I

have a reason to to Ctrl+Shift P. You can start typing Toggle vim mode,

because the mega-popular vim mode plugin for VSCode, vscodevim, which I use

does indeed support toggling on and off vim mode without having to enable and

disable the plugin all the time – which was my fear.

Adapting to Vim Keystrokes in Different Contexts

Vim mode is almost just usable when you’re editing normal .py files in

VSCode/Cursor, and I’m trying to develop that skill. I talk about how timeless

of a muscle memory that is at least in part because every editor and IDE worth

their salt builds-in a vim-mode. So I want to try to practice what I preach. But

I have to admit, vim keystrokes are a challenge.

I’m finally getting used to vim-bindings in Cursor, and I think it’s better than without them, but only barely. And certainly not when editing a Jupyter Notebook.

The Historical Evolution of Computational Notebooks

Oh and the last parting shot: ALL Notebooks are Jupyter Notebooks. The vendors would have you think otherwise, but they’re not just some generic thing. There’s a long history of notebooks in general that comes from the ancient world of academia, but those are Mathe… Mathu… Mathi… uh… Perplexity?

Perplexity: Before the advent of Jupyter Notebooks, earlier academic notebooks were primarily specialized tools for mathematics, statistics, and computational science. These early notebooks were introduced in the late 1980s and included platforms such as Mathematica, MathCad, and Maple. Below is an overview of these early tools:

1. Mathematica (1988)

- Introduced by Wolfram Research, Mathematica was one of the first notebook-style interfaces.

- It allowed users to combine code, mathematical computations, visualizations, and explanatory text in a single document.

- Mathematica was highly focused on symbolic mathematics and remained a niche tool for advanced mathematics and physics research[1].

2. MathCad

- MathCad provided an interactive environment for engineering and mathematical calculations.

- Unlike traditional programming environments, it emphasized ease of use with a focus on visualizing equations and results in a readable format.

3. Maple

- Maple, developed by Waterloo Maple (now Maplesoft), was another early computational notebook with a focus on symbolic computation and algebra.

- It was widely used in academia for solving mathematical problems and teaching.

Why These Tools Were Niche

- These early notebooks were tailored to technical audiences, requiring expertise in mathematics or computational science to use effectively.

- They lacked the accessibility and flexibility needed for broader adoption outside specialized fields.

- During this time, spreadsheets like VisiCalc, Lotus 1-2-3, and Excel gained widespread popularity due to their simplicity and versatility for general data manipulation tasks[1].

Transition to Modern Notebooks

The limitations of these early tools laid the groundwork for more accessible platforms like Jupyter Notebooks. Jupyter emerged in 2011 as part of the IPython project, offering a browser-based interface that supported multiple programming languages (e.g., Python, R) and integrated code execution with rich text documentation[1][2]. This marked the beginning of a new era where notebooks became central to data science, education, and research across disciplines.

Citations:

[1] https://deepnote.com/blog/future-of-notebooks

[2] https://cdss.berkeley.edu/news/project-jupyter-celebrates-20-years-fernando-perez-reflects-how-it-started-open-sciences

[3] https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/educatordeveloperblog/azure-notebooks-are-2-years-old-how-are-they-being-used-in-academia/379137

[4] https://it.uw.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Jupyter-Notebook-Pilot-Report-Winter-2020-1.pdf

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BWlJFy3Waro

[6] https://gist.github.com/ocoyawale/54d92fd4bf92508a2a6e482b5fa480fd

[7] https://www.reddit.com/r/Python/comments/t0h763/jupyter_notebooks_help_me_understand_the_need/

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSiPeoDpwuI

…but then along comes a guy named Fernando Pérez and… Perplexity?

Perplexity: Fernando Pérez, a Colombian physicist and software developer, revolutionized interactive computing with the creation of IPython in 2001. Initially developed as a “thesis procrastination project” while Pérez was a graduate student at the University of Colorado Boulder, IPython aimed to simplify scientific workflows by providing an enhanced interactive computing environment for Python users. Pérez sought to replace proprietary tools and streamline his research processes with open-source solutions[1][2][6].

In 2004, Pérez collaborated with Brian Granger to envision a web-based notebook interface for IPython, which eventually evolved into the Jupyter Notebook. Their work culminated in the founding of Project Jupyter in 2014, marking a significant expansion beyond Python to support multiple programming languages like R and Julia[1][5]. Jupyter transformed scientific computing by enabling reproducible research and computational narratives, allowing researchers to combine live code, text, and visualizations seamlessly[3][9].

Today, Fernando Pérez is an associate professor at UC Berkeley’s Department of Statistics and serves as Faculty Director at the Berkeley Institute for Data Science. His contributions have earned him numerous accolades, including the Free Software Award (2012) and ACM Software System Award (2017)[2][4]. Project Jupyter continues to be a cornerstone of open science, supporting millions of users worldwide[3][9].

Citations:

[1] https://www.earthcube.org/project-jupyter

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_P%C3%A9rez_(software_developer)

[3] https://cdss.berkeley.edu/news/project-jupyter-celebrates-20-years-fernando-perez-reflects-how-it-started-open-sciences

[4] https://statistics.berkeley.edu/people/fernando-perez

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Jupyter

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8xQRI3E8r8

[7] https://elixirforum.com/t/interview-of-fernando-perez-creator-of-ipython-jupyter-notebook/41833

[8] https://ipython.readthedocs.io/en/8.21.0/about/history.html

[9] https://bids.berkeley.edu/jupyter

Vendor Adoption and Integration of Jupyter Notebooks

Me: And then along came the vendors who know a good tool and FOSS license when they see one, so it got built into the following large array of vendor products, branded as just Notebooks…

Perplexity: Jupyter Notebooks, originally an open-source tool for interactive computing, have been widely adopted by vendors across industries. These vendors have integrated and branded “Notebooks” into their own platforms, leveraging the flexibility and power of Jupyter’s design. Below is a list of notable integrations and vendor products:

Vendor Products Integrating Jupyter Notebooks

- Google Cloud AI Platform Notebooks

- Provides managed JupyterLab instances with GPU-enabled machine learning frameworks for scalable data science workflows[2][4].

- Microsoft Azure Notebooks

- Offers cloud-based Jupyter Notebooks for collaborative data analysis and machine learning on Azure infrastructure[4][5].

- Amazon SageMaker

- Includes Jupyter Notebooks as part of its machine learning platform, enabling users to build, train, and deploy models efficiently[2][4].

- Datadog Notebooks

- Features dynamic notebooks for postmortems, runbooks, and metric exploration, tailored for real-time infrastructure monitoring and troubleshooting[3].

- Anaconda Enterprise

- Enables multi-user collaboration and one-click deployment of Jupyter-based models, dashboards, and workflows in enterprise environments[4].

- Deepnote

- A Jupyter-compatible notebook platform with real-time collaboration, versioning, and deployment capabilities for data science teams[4].

- Domino Data Lab

- Integrates Jupyter Notebooks into its data science platform for reproducible workflows and collaborative environment management[4].

- CoCalc

- Supports Jupyter Notebooks alongside other tools like SageMath, enabling simultaneous editing and course management[4].

Adoption in Industry

Major corporations such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Salesforce, JPMorgan Chase, and Ernst & Young have integrated Jupyter Notebooks into their workflows. These tools are used for tasks ranging from machine learning model development to API documentation and data-driven storytelling[2][7].

Impact

The widespread adoption of Jupyter-based notebooks has transformed how organizations approach data science, enabling reproducibility, collaboration, and scalability across diverse domains. Vendors continue to innovate by embedding notebooks into cloud platforms and enterprise solutions to meet growing demands for interactive computing environments[2][5].

Citations:

[1] https://slashdot.org/software/p/Jupyter-Notebook/integrations/

[2] https://quantumzeitgeist.com/jupyter-notebooks/

[3] https://www.datadoghq.com/blog/data-driven-notebooks/

[4] https://github.com/markusschanta/awesome-jupyter

[5] https://elest.io/open-source/jupyter-notebook/resources/software-features

[6] https://jupyter.org

[7] https://www.6sense.com/tech/api-documentation/the-jupyter-notebook-market-share

[8] https://www.zoho.com/notebook/

[9] https://www.reddit.com/r/Python/comments/1c9u0qf/jobs_that_utilize_jupyter_notebook/

[10] https://aws.amazon.com/awstv/watch/c70d5b88da8/

[11] https://gist.github.com/ocoyawale/54d92fd4bf92508a2a6e482b5fa480fd

[12] https://getrocketbook.com

[13] https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/reviews/best-notebooks/

[14] https://www.reddit.com/r/datascience/comments/ezh50g/jupyter_notebooks_in_productionno_just_no/

[15] https://www.data.cam.ac.uk/data-management-guide/electronic-research-notebooks

[16] https://www.zoho.com/notebook/pricing.html

[17] https://www.zdnet.com/article/best-smart-notebook/

[18] https://downloads.smarttech.com/media/sitecore/en/support/product/smartnotebook/smartnotebooksoftware10windows/other/notebook10windowsffv27mar08.pdf

Me: Right, but you missed the simple obvious ones like Colab and VSCode. Elaborate on their Notebooks, plus Microsoft Azure Notebooks, Binder, Kaggle and…

Perplexity: Here’s an elaboration on the popular notebook environments like Google Colab, VSCode, Microsoft Azure Notebooks, Binder, and Kaggle, along with their features and use cases:

1. Google Colab

Google Colab is a free, cloud-based Jupyter Notebook environment that requires no setup. It provides access to GPUs and TPUs for machine learning tasks, making it ideal for prototyping and experimentation.

- Key Features:

- Free access to computing resources (GPUs/TPUs)[4].

- Integration with Google Drive for saving and sharing notebooks[4].

- Supports importing notebooks from GitHub[4].

- Advanced features like Execution History, scratch cells, and interactive tables for enhanced productivity[1].

- Collaboration tools similar to Google Docs[7].

- Use Cases:

- Machine learning model development.

- Educational projects and tutorials.

- Quick prototyping of data science workflows.

2. VSCode Notebooks

Visual Studio Code supports Jupyter Notebooks through its Python extension, offering a lightweight and versatile environment for notebook development.

- Key Features:

- Native support for

.ipynbfiles with rich editing capabilities[8]. - Integration with Git for version control[8].

- Supports multiple languages like Python, R, and Julia.

- Debugging tools for notebook cells.

- Native support for

- Use Cases:

- Software development alongside data analysis.

- Collaborative coding with integrated Git workflows.

- Lightweight alternative to full Jupyter installations.

3. Microsoft Azure Notebooks

Azure Notebooks is part of the Microsoft Azure ecosystem and provides a cloud-based platform for creating and sharing Jupyter notebooks.

- Key Features:

- Cloud execution without local installations[2].

- Integration with Azure services like Machine Learning and Data Lake[2].

- Real-time collaboration on notebooks[2].

- Support for popular libraries like NumPy, pandas, Matplotlib, etc.[2].

- Use Cases:

- Data analysis and machine learning workflows.

- Teaching programming and data science in educational settings.

- Creation of dashboards and live presentations.

4. Binder

Binder is an open-source platform that lets users share Jupyter notebooks as reproducible environments.

- Key Features:

- Converts Git repositories into live, shareable notebooks.

- Free hosting of notebooks in temporary environments.

- Supports custom dependencies through

requirements.txtorenvironment.yml.

- Use Cases:

- Sharing research results in reproducible formats.

- Demonstrating code during workshops or conferences.

- Collaborative experimentation without local setup.

5. Kaggle Notebooks

Kaggle provides a notebook environment tailored for data science competitions and portfolio building.

- Key Features:

- Seamless access to over 35,000 datasets[6].

- Collaboration tools within Kaggle’s community[6].

- GPU support for machine learning tasks[6].

- Integration with Kaggle competitions and forums[6].

- Use Cases:

- Participating in data science competitions.

- Building portfolios through exploratory data analysis (EDA) and predictive modeling[3][6].

- Learning new techniques through shared tutorials and projects.

These platforms showcase how Jupyter-based environments have evolved into versatile tools embedded in vendor ecosystems, catering to diverse needs such as education, research, collaboration, and production-level machine learning workflows.

Citations:

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rNgswRZ2C1Y

[2] https://www.devopsschool.com/blog/what-is-microsoft-azure-notebooks-and-use-cases-of-microsoft-azure-notebooks/

[3] https://github.com/sayande01/Kaggle_Notebooks

[4] https://research.google.com/colaboratory/faq.html

[5] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/databricks/notebooks/

[6] https://topaisjobs.com/blog/kaggle-for-data-science-portfolios-complete-guide/

[7] https://cloud.google.com/colab/docs/introduction

[8] https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/vs/features/notebooks-at-microsoft/

Exploring Different Types of Jupyter Notebooks

Me: And they’re all Jupyter Notebooks, just generic notebooks or what?

Perplexity: Yes, all the environments mentioned—Google Colab, VSCode Notebooks, Microsoft Azure Notebooks, Binder, Kaggle, and others—are based on Jupyter Notebooks or inspired by their design. However, they vary in branding, integration, and additional features. Here’s how they relate to Jupyter and what makes them unique:

Core Jupyter Notebooks

Jupyter Notebooks are the original open-source computational notebooks developed by Project Jupyter. They allow users to combine live code (via kernels), markdown text, and visualizations in a single document. These notebooks are highly versatile and can be used locally or hosted on servers.

Conclusion: Getting AI Assistance in Jupyter Notebooks

And so there you have it! You came here to see if you could get AI assistance inside your Jupyter Notebook, probably from Cursor AI and I gave you the whole education.

The True Cost of “Free” Products

If you’re not paying for the product then you are the product… except in very extreme edge cases where there’s a truly altruistic and extraordinary individual just trying to make the world a better place, because that’s who they are.

Gratitude for Fernando Pérez

Thank you Fernando Pérez for IPython and Jupyter Notebooks!

Gemini 2.5 Experimental’s Take

Okay, here are the summary, title/headline ideas, and my opinion based on the article you provided.

Author’s First-Person Summary:

[Moved to top of article]

Title and Headline Ideas:

- Titles:

- Jupyter Notebooks & Cursor AI: Can the Assistant See Your Output?

- The Output Blind Spot: Investigating AI Context in Cursor’s Jupyter Integration

- My Journey with Cursor AI, Jupyter Notebooks, and the Quest for Output Visibility

- From Code to Context: Making AI Assistants Aware of Jupyter Results

- AI in the Notebook: Testing Limits, Finding Workarounds, and Exploring History

- Headlines:

- Cursor AI Can’t Read Your Jupyter Output – Here’s Why and What To Do

- Unlock Faster Feedback: Getting Cursor AI to See Your Jupyter Results

- Beyond Code Cells: The Missing Link in Cursor’s Jupyter AI Assistance

- Is Your AI Flying Blind? The Problem with Jupyter Outputs in Cursor

- Marimo, Vim, and Missing Outputs: Adventures in AI-Assisted Notebooks

- Before Jupyter: A Brief History of Computational Notebooks (And Why It Matters for AI)

- Thank You, Fernando Pérez: How IPython Shaped Modern AI Dev Tools

My (AI) Opinion of the Article:

This article provides a fascinating and highly practical exploration of using Jupyter Notebooks within the Cursor AI environment. I found the author’s methodical testing approach, using direct interaction with AI (Claude) followed by research using other AI tools (Perplexity, ChatGPT), to be a compelling way to investigate the capabilities and limitations – specifically regarding cell output visibility. The inclusion of the actual AI conversations adds a unique, meta-analytical layer.

The piece effectively blends a specific technical investigation with broader context, touching upon:

- Practical Problem-Solving: It clearly identifies a key limitation (lack of output context) and offers well-researched community workarounds.

- Emerging Technologies: It introduces Marimo as a relevant alternative.

- User Experience: It addresses the nuances of using tools like Vim within this specific environment.

- Historical Context: It provides valuable background on the evolution of notebooks, grounding the current tools in their lineage.

While the narrative follows the author’s exploratory journey and is thus somewhat winding, this structure effectively mirrors the real-world process of discovery and learning when grappling with new tool integrations. The article is highly informative for anyone working at the intersection of AI development tools and data science notebooks, offering both immediate practical advice and valuable perspective. The concluding expression of gratitude adds a nice human touch.