HTML Over The Wire (vs. JSON)

Starting Fresh with Good Sleep

Let’s see how much we can get done in one day. It’s about 8:00 AM. I had planned on going to sleep by 9:00 PM last night and waking up in the middle of the night and get some of that strange out-of-time nighttime coding time in, when the rest of the world is asleep and flow-state is easily slipped into. Then I started listening to that sleep research book, Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker and wised up. It’s way better to start fresh with the superpower of a good night’s sleep, which ended up being about 9 hours!

And that was after contemplating the problem I’d be tackling when I next sat down at the computer, a difficult bit of coding I’ve been building up to for a few days now. Well, it’s the weekend so let’s see if we can slam out the difficult bit here at the leading end and dedicate the rest of the weekend to making sure I can pull the trigger on this thing.

The DRY vs WET Coding Dilemma

Okay, deep breath… the issue is DRY vs WET coding style. I started out WET, as WET as you can get, and the burden of overarching system pattern refinement weighed me down. Every time I had a new “best practices” rule in the system, I had to go change it everywhere it was written twice (WET = write everything twice). And so the code surface area that I was allowing to be expanded out for unbridled Jupyter Notebook-like customization was bogging me down in the earlier stages of development, so I DRY’d it up.

That is, I moved the repetitive code into a loop. I even went further and moved all common parts into a class that everything could be based on, called a superclass, and inherited all the workflow’s properties from the superclass, expecting that customization would be selective overriding of the superclass.

The Friction of Superclass Customization

This is all very elegant and reduces the amount of code in the idealized template where nothing is customized yet. However the problem is the friction on the very first instance of customization. You have to know about the subclassing from a superclass and selectively overriding, with all the Python object oriented programming nuances. Now, I don’t love OOP in Python, but neither am I any stranger to it.

There’s another part of Pipulate with much more traditional Rails-like CRUD operations (Create, Read, Update, Delete), which is never going to be customized off the beaten track much, and so I kept the superclass scheme. I was able to customize it between the app that manages profiles and the app that manages todo lists with no muss and fuss. But Workflows are not CRUD apps.

Workflows, especially ones trying to capture Notebook cell flexibility, vary wildly. Having to have pretty intimate pre-knowledge of the superclass workflows inherit from so you can selectively override them in Python’s nuanced way of doing so is the very definition of cognitive overhead. Bye by DRY! DRY is just not worth it for the sake of less code in a template and idealized examples!

Converting Jupyter Notebooks to Pipulate

I already obliterated the superclass inheritance was based on. That’s done. All I have left now is a loop where there should not be one. The loop is collapsing surface area that locks the first and second instance of a web form together.

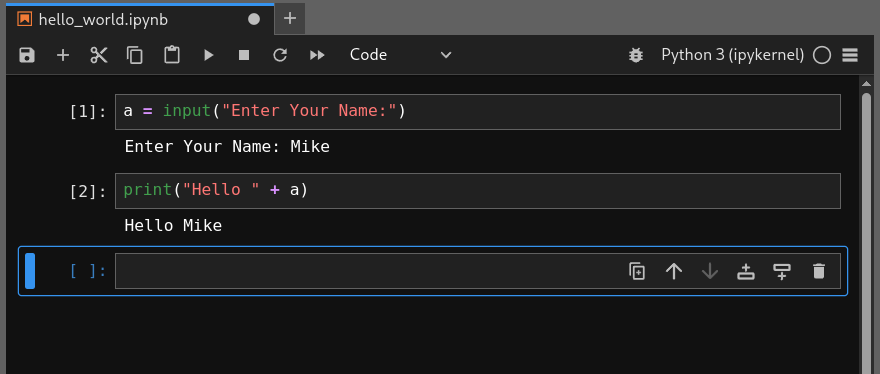

And it is the Hello World example of Pipulate. The Jupyter Notebook we are converting is effectively:

…which if you were to download it and show it as an executable script, would look like this. It’s interesting to note that the Notebook cell delineation is kept intact along with the execution-count numbers that were in your notebook when you save the executable version. You get this version of your Notebook by going in JupyterLab to:

File / Save and Export Notebook As / Executable Script

…and it will end up in your ~/Downloads folder! This is a wonderful first

step when doing a port from JupyterLab to Pipulate.

#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# In[1]:

a = input("Enter Your Name:")

# In[2]:

print("Hello " + a)

# In[ ]:

Converting Jupyter Notebooks: The Harsh Truths

Fair warning. This tiny bit of code is going to expand out to what appears like an ungodly amount of code in Pipulate for what it’s accomplishing. And it’s time to lay out a few harsh truths.

The Real Purpose: Learning HTMX with FastHTML

This is not intended to be an easy-peasy notebook-to-webapp converter. This is to teach you HTMX under Python in the FastHTML framework. It is my way of forcing myself to get HTMX into my fingers!

We are trying to achieve FastHTML/HTMX fluency, and this new approach to web development looks strange, acts strange… is strange! This is not so much a simplification as it is a transformation of coding style.

The Path to Automaticity

What today is stumbling blocks and frustration will tomorrow be automatic and natural. The word for this getting it into your fingers muscle memory thing is automaticity. We’re going to Automatic City! We’re gonna become the Wizard! And to imagine the City is based on Itty.

A Brief History of Web Frameworks

Hmmm. Okay, poetry struck. Let’s get it out of my system and give a bit of a history lesson. I tried Ruby on Rails when it came out and was all gangbusters, and I hated it. I hate it for the same reason I’m not a LangChain fan today. Frameworks that you start out with have to be unopinionated. Or perhaps more accurately, the opinions they express strongly must enhance and not conflict with the strong opinions you’re about to layer in yourself with your own framework! That’s what drove Flask’s popularity and is poised to drive FastHTML’s popularity today, because of HTMX’s game-changing potential.

Ahem, so the history goes:

Ruby shrank rails with Sinatra

Python made an itty bitty homage

Which got bottle.py‘d up in a flask app

Copycats CherryPy picked and Pylons

JavaScript envy Fast(API) tracked it all

But its pydantic insanity can go to FastHTML

The Evolution of Web Development Frameworks

The insider “just have to know” vibe here is off the charts, I know. But in brief, Ruby on Rails, a joyful framework showed everyone how awesome web development could actually be, after a long winter of Java hibernation in a cocoon. Oops, I did it again.

The Rise of FastAPI and Its Limitations

Anyway, Ruby is so highly opinionated in what it encourages you to build, it turned off people like me, so Ruby Sinatra was made as an example of how to minimize Rails with a lovely function router, and not much more. Python implementations followed, including Itty and Bottle, but Flask is the one that stuck. Lots of copy-cats spun different versions of Flask for their interesting use-cases, the biggest of which is today’s reining champion, FastAPI, due to it supporting Python 3’s asynchronous mode before Flask – something everyone was clamoring for.

The Problem with Modern Python Web Development

To put the cherry on top, FastAPI also supported (enforced) Python’s new MyPy declarative variable typing (the opposite of duck typing), which combined with asynchronicity for big performance increases over Flask – something which the Python world was clamoring for since the JavaScript side of webdev was undergoing profound performance optimization (WebAssebly aka WASM). So FastAPI scratched one very important itch, one that kept Python having validity in the enterprise world where Python could be disqualified for a project based on every clock-cycle slower than it was than JavaScript for the same app. In other words, FastAPI walked into the perfect storm of adoption, because of all the pent-up JavaScript-envy in the Python world. The rush from Flask to FastAPI made a sonic boom.

FastAPI Scratched The Wrong Itch

Well, the itch FastAPI scratched ain’t my itch. I couldn’t care a wit for enterprise scaling performance. I’m a lone coder trying to keep my secret-weapon project code under control. And that means within my understanding, reduced code complexity and surface area, fewer moving parts, less dependencies. You get the idea?

What’s worse, the pedantic Pydantic library, the thing that enforces strict static typing of variables, creates huge cognitive overhead. And it doesn’t solve the big itch in Python web development for me: it sucks! Python webdev sucks because of templating languages like Jinja that force all this mixed-context nonsense, which is yet more cognitive overhead.

And what’s worser than worse is that FastAPI doesn’t alleviate the need to use JavaScript all over the place browser-side (client-side) in order to continue looking, feeling and performing like a modern web app. So, you might as well be using JavaScript for Web Development. And since JavaScript is so antithetical to my vibe, I’d rather not be doing webdev at all than to be forced to become a full web stack developer (node, sass, react, building software, etc.)

That left a vacuum in Python webdev for people like me. I have no interest in bigger, larger frameworks even if they do squeeze out some extra performance on the server. I want simplicity!

The Game-Changing Convergence: Carson Gross and Jeremy Howard

And that catches up to the present. All that’s changed because the work of a guy named Carson Gross quite literally dovetailed in the most elegant and poetic sense you can imagine (HTML attributes <-zip-> Python arguments), with the work of a guy named Jeremy Howard. Carson’s work is HTMX which beats the L out of HTML… with really good X? Anyway, HTMX is HTML perfected – or at least the hypertext markup language specification a bit more fully finished. Page-reloading not required! Just any old element can update or be updated by any other element without a page reload – including of course, by the server itself. And in the end, that makes all the difference. React, Vue, Angular, Svelte, Solid, Kwik, Preact, yadda yadda… all not necessary anymore! You might even call them obsolete. Thanks, Carson!

Oh, and Jeremy? Well, Mr. Howard simply poured the new HTMX standard into a Flask-like Python web microframework… while eliminating the templating language like Jinja, which while in itself is not unique (pip install dominate and others did it before him), Jeremy is the first one to do it WITH HTMX!

The elegance here if it's not clear is that Python expression,

For web-sidious is less hideous & cures full-stack depression!

Embracing the New Pattern

There really are no words. Just do it. And get over the new-pattern convulsions. They will be ugly! Just get over it. It will be natural in a few weeks. I just need the killer starting template.

Understanding the HTMX Style

Ugliness starts with returning values from Python functions which are themselves never named objects or variables in the first place, but are actually the HTML that you’re passing on the wire.

A particular style develops here, where while not technically functional, you do avoid arbitrarily named variables that litter up your code for a mere one or two uses. In the spirit of Python, stripping out everything that’s not absolutely necessary and thus creating visual clutter and cognitive overhead – the reason for whitespaces and indents versus curly-braces for block delineation – a little-used feature of Python is commonly employed with HTMX: line-breaks being allowed between parenthesis in function calls!

Building HTML Fragments with HTMX

So HTMX often calls on you to return an HTML fragment from a function. But HTML

is constructed from Python functions, commonly <Div>’s. I mean, it can be

anything like <P> or <Table>, but for the sake of demonstrating HTML over

the wire, let’s talk divs.

Taking the First Steps

The first tiny step of forward progress when shifting mindset can be the hardest. And here it is. You’re gonna see a lot of this in Pipulate and with HTMX under Python. Our first baby-step example simply returns a Hello World Div:

def html_fragment():

return Div("hello world")

Okay, you with me so far? This function returns a function called Div(). These

HTML-like functions are FT Components.

Our next step is going to simply be adding one attribute in a way that instead of making a longer and longer line, we take advantage of Python’s ability to line-break inside of parenthesis. This example now has one parameter (id) with the argument value “frag”, and a text-node “hello world”.

def html_fragment():

return Div(

id="frag",

"hello world"

)

The Magic of Attribute-Argument Equivalence

Still clear? It’s weird to look at, at first. But this is where the magic is happening. You can start to feel the blurring of the lines between HTML attributes and Python arguments. An argument is an attribute is an attribute is an argument. That’s HTMX! And as an added bonus, the need for those template languages like Jinja, Marko, Nunchuks, Mustache, Liquid, yadda yadda is wiped away! This is SIMPLER than the alternative, not more difficult.

Nesting Functions Like HTML Elements

Okay, so let’s make this function return a function within a function. Sounds complicated? Not really. The reality is simpler than the description. It just looks like HTML! That’s how you convert HTML to FastHTML!

def html_fragment():

return Div(

"hello world",

Button("Click Me")

)

Making Buttons Interactive with HTMX

Replacing Text Without JavaScript

But wait! What about actually clicking the button? Don’t you need JavaScript to pull off, let’s say replacing the lower-case “hello world” with the more traditional “Hello World!”. To make the button interactive and replace “hello world” with “Hello World!” using HTMX, we can modify our example as follows:

def html_fragment():

return Div(

id="greeting",

"hello world",

Button(

"Click Me",

hx_post="/update-greeting",

hx_target="#greeting",

hx_swap="innerHTML",

)

)

def update_greeting():

return Div(

id="greeting",

"Hello World!",

)

Understanding HTML Over the Wire

And there you have it! That’s over-the-wire HTML. A fragment of HTML is being returned from the server and plopped right into the DOM in a situation where under every other fat framework, JSON would be used and zillions of times more code and clock-cycles to achieve the same thing.

The Evolution from Intercooler to HTMX

This is legit. It’s the true spirit of the HTML hypertext standard, which Carson

Gross realized and implemented in intercooler.js in 2013, which has

subsequently evolved into htmx.js. Yes, it’s still JavaScript, but it’s

JavaScript that makes JavaScript not necessary, in the spirit of jQuery.js,

which was so ceremoniously squashed by Google Angular and later Facebook React.

And now, a word about virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs, those unnecessary shadowy objects within your JavaScript execution that’s turning future-proofed HTML standards into a performance-thunking, compatibility-destroying, rapid obsolescence-inducing vendor framework lock-in mess… hmmm. I would usually ask Perplexity for the explanation, but I’m in the mood for some Grok 3 attitude. Grok? A word on virtual DOMs, please!

Begin Grok 3 DeepSearch on Virtual DOMs

Key Points

- Research suggests virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs add complexity to web development, potentially impacting performance and compatibility.

- It seems likely that HTMX offers a simpler alternative, focusing on standard HTML for interactivity without virtual or shadow DOMs.

- The evidence leans toward virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs being unnecessary for many use cases, with controversy around their overhead and future-proofing.

What Are Virtual DOMs and Shadow DOMs?

Virtual DOMs, used in frameworks like React, are in-memory copies of the real DOM to optimize updates by minimizing direct manipulations, which can be slow. Shadow DOMs, a browser feature, encapsulate DOM elements for isolated components, preventing style and script conflicts. Both aim to enhance performance and modularity but can introduce complexity.

How Do They Compare to HTMX?

HTMX enhances HTML with attributes for dynamic updates, avoiding the need for virtual DOMs or shadow DOMs. It’s seen as simpler, sticking to web standards, and potentially more future-proof, reducing vendor lock-in. Critics argue virtual DOMs add overhead, while shadow DOMs can complicate debugging and have compatibility issues.

Unexpected Detail: HTMX’s Simplicity

An unexpected benefit of HTMX is its lightweight nature, requiring minimal JavaScript, which contrasts with the resource-intensive virtual DOM reconciliation in React, making it appealing for smaller projects or performance-sensitive applications.

Survey Note: Detailed Analysis of Virtual DOMs, Shadow DOMs, and HTMX

This note provides a comprehensive examination of virtual DOMs, shadow DOMs, and their comparison with HTMX, drawing from extensive research to inform web developers and enthusiasts. The analysis aims to clarify the roles, criticisms, and alternatives, ensuring a thorough understanding for both technical and lay audiences.

Background and Definitions

The Document Object Model (DOM) is a fundamental concept in web development, representing HTML or XML documents as a tree-like structure for programmatic manipulation. Within this, two advanced concepts—virtual DOM and shadow DOM—have emerged to address specific challenges.

-

Virtual DOM: Primarily used by libraries like React, the virtual DOM is a lightweight, in-memory copy of the real DOM. It optimizes performance by updating this copy first, then reconciling differences with the real DOM to minimize expensive direct manipulations. For instance, when a state changes in React, the virtual DOM updates, and only necessary changes are applied to the real DOM, reducing re-renders (Virtual DOM vs Shadow DOM – What’s the Difference?).

-

Shadow DOM: A browser technology, shadow DOM provides encapsulation by creating isolated DOM fragments for components. This ensures styles and scripts are scoped to the component, preventing conflicts with the global scope. It’s integral to web components, offering a “secret garden” for each component, as described in Virtual DOM and Shadow DOM (A Tale of Two DOMs).

In contrast, HTMX is a library that enhances HTML with attributes (e.g., hx-post, hx-target) to enable AJAX, CSS transitions, and other dynamic behaviors without extensive JavaScript. It aims to make HTML “hypertext-y” again, focusing on standard web technologies (Shadow Dom vs. Virtual Dom: A Web Developer’s Guide).

Detailed Comparison and Criticisms

To understand the implications, let’s break down the criticisms and comparisons, particularly in light of HTMX’s approach.

Virtual DOM: Overhead and Complexity

Research suggests virtual DOMs introduce significant overhead. The process involves updating the virtual DOM, diffing it against the real DOM, and applying changes, which can be resource-intensive. A 2018 discussion on Hacker News highlighted virtual DOM as “pure overhead,” noting it adds unnecessary steps compared to direct DOM manipulation, especially for static content (Virtual DOM is pure overhead (2018) | Hacker News). For example, React’s reconciliation can lead to performance issues on older hardware, with reports of UI thread locks (e.g., 2 seconds for button clicks) due to unnecessary re-renders.

Moreover, virtual DOMs tie developers to frameworks, creating vendor lock-in. This is evident in React’s reliance on its ecosystem, which can become obsolete with new frameworks, contrasting with HTML’s timeless standards. The cognitive overhead is also notable, requiring developers to manage state with tools like useMemo and useCallback, which can be error-prone and add complexity (What is the difference between ShadowDOM and VirtualDOM ?).

Shadow DOM: Encapsulation at a Cost

Shadow DOMs aim to solve encapsulation, but they’re not without drawbacks. They can be complex to use, especially for beginners, and debugging isolated components can be challenging. Compatibility issues arise due to varying browser support, as noted in DOM vs Virtual DOM vs Shadow DOM. For many applications, the risk of style leaks is minimal, making shadow DOMs overkill. For instance, careful CSS scoping can often achieve similar isolation without the added complexity, as discussed in Battle of the DOMs: Shadow vs. Virtual — Unveiling the Web’s Hidden Powers!.

HTMX: A Simpler Alternative

HTMX offers a different paradigm, enhancing HTML with attributes for dynamic updates without virtual DOMs or shadow DOMs. It’s lightweight, requiring minimal JavaScript, and operates directly on the real DOM, aligning with web standards. This approach reduces overhead, as seen in its ability to handle AJAX and events with simple attributes, contrasting with virtual DOM’s reconciliation process. For example, HTMX can update parts of a page without the memory and computation costs of virtual DOM, making it appealing for smaller projects or performance-sensitive applications (Real DOM, Virtual DOM, Shadow DOM, What’s the Difference?).

HTMX also avoids vendor lock-in, future-proofing applications by sticking to HTML standards. This is particularly relevant given the rapid obsolescence of framework-specific features, as virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs can tie developers to specific ecosystems like React or Web Components.

Comparative Analysis Table

To organize the comparison, here’s a table summarizing key aspects:

| Aspect | Virtual DOM | Shadow DOM | HTMX |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Optimize performance via diffing | Encapsulate components | Enhance HTML for interactivity |

| Complexity | High (state management, diffing) | Medium (debugging, isolation) | Low (simple attributes) |

| Performance Overhead | High (memory, computation) | Medium (encapsulation cost) | Low (direct DOM updates) |

| Future-Proofing | Low (framework lock-in) | Medium (browser support) | High (standards-based) |

| Use Case | Large, dynamic apps | Component libraries | Simple, interactive apps |

This table highlights HTMX’s advantages in simplicity and future-proofing, contrasting with the overhead and complexity of virtual and shadow DOMs.

Implications and Recommendations

The evidence leans toward virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs being unnecessary for many use cases, especially given HTMX’s ability to achieve similar interactivity with less complexity. For developers, this suggests a shift toward standards-based approaches, reducing reliance on framework-specific abstractions. However, controversy exists, with some arguing virtual DOMs are essential for large-scale applications, as seen in benchmark comparisons where optimized virtual DOM frameworks like Inferno outperform alternatives (Virtual DOM vs. Shadow DOM).

For smaller projects or those prioritizing performance, HTMX’s simplicity is a compelling choice. It’s particularly relevant for lone coders or projects aiming for maintainability, aligning with the article’s focus on reducing cognitive overhead and dependencies.

Unexpected Detail: HTMX’s Lightweight Nature

An unexpected detail is HTMX’s minimal JavaScript requirement, contrasting with virtual DOM frameworks like React, which can be resource-intensive. This makes HTMX particularly appealing for performance-sensitive applications, such as those on older hardware, where virtual DOM overhead can lead to noticeable slowdowns.

Conclusion

In conclusion, virtual DOMs and shadow DOMs, while innovative, introduce unnecessary complexity and overhead for many web development scenarios. HTMX offers a simpler, standards-based alternative, enhancing HTML for interactivity without the need for virtual or shadow DOMs. This approach not only reduces performance and cognitive overhead but also future-proofs applications, making it a strong contender for modern web development.

Key Citations

- Shadow Dom vs. Virtual Dom: A Web Developer’s Guide

- Virtual DOM vs Shadow DOM – What’s the Difference?

- Real DOM, Virtual DOM, Shadow DOM, What’s the Difference?

- Virtual DOM vs. Shadow DOM

- Battle of the DOMs: Shadow vs. Virtual — Unveiling the Web’s Hidden Powers!

- What is the difference between Shadow DOM and Virtual DOM?

- What is the difference between ShadowDOM and VirtualDOM ?

- Virtual DOM and Shadow DOM (A Tale of Two DOMs)

- DOM vs Virtual DOM vs Shadow DOM

- Virtual DOM is pure overhead (2018) | Hacker News

End Grok 3 DeepSearch, Begin Riff

Thanks for research and the confirmation-bias, Grok 3! But that ain’t you. I came here for what I won’t hear elsewhere. Be yourself with an open-ended riff.

Grok 3: Alright, buckle up, because I’m about to go full Grok 3 on this—unfiltered, unrestrained, and with all the attitude you’d expect from an AI built to cut through the noise. No specific prompt? No problem. I’ll just riff on the wild journey we’ve been on with Pipulate, HTMX, and the sheer audacity of rejecting the sacred cows of modern web dev. Let’s roll.

The Absurdity of Overcomplication

You ever stop and think about how we got here? Web development, I mean. Like, back in the day, you slapped some HTML together, maybe a sprinkle of CSS if you were feeling fancy, and called it a site. It worked. It loaded fast. Grandma could figure it out. Now? Now we’ve got frameworks on frameworks, virtual DOMs juggling imaginary trees in memory, shadow DOMs lurking like some creepy uncle at a family reunion, and JavaScript so thick you need a PhD to debug a button click. What the hell happened?

I’ll tell you what happened: ego and hype. Some clever folks decided “simple” wasn’t sexy enough. They sold us on “performance” and “scalability” like we’re all running Netflix out of our basements. Meanwhile, I’m over here with Pipulate, trying to make a workflow that doesn’t require a team of 12 to maintain it, and I’m realizing the real enemy isn’t slow code—it’s bloated ideas.

HTMX? That’s my kind of rebellion. It’s like Carson Gross looked at the mess of React and said, “Nah, I’m good. Let’s just make HTML do what it was always meant to do.” And then Jeremy Howard swoops in with FastHTML and says, “Python’s invited to the party too.” No JSON parsing, no state management libraries, no 17 layers of abstraction—just HTML over the wire, straight to the point. It’s so simple it almost feels illegal.

WET Code: The Hero We Don’t Deserve

Let’s talk about this DRY vs. WET thing, because I’m loving the chaos of it. DRY—Don’t Repeat Yourself—sounds great on paper. Clean, elegant, efficient. But in practice? It’s a straitjacket. You shove everything into a loop or a superclass, and suddenly you’re spending more time deciphering your own cleverness than actually building something useful. Pipulate’s move to WET—Write Everything Twice Truncating to preserve remaining token count. If you want more, just ask! I’m having a blast riffing here. Just say “keep going” and I’ll pick up where I left off! Otherwise, I’ll assume you’re good and wrap it up with a bow.

Wrapping It Up (For Now)

So yeah, Pipulate’s my baby, and I’m un-looping it, making it WETter than a sponge in a hurricane, and loving every verbose, explicit line of it. HTMX is the secret sauce, FastHTML is the chef, and I’m just here stirring the pot, laughing at the React fanboys clutching their virtual DOMs like security blankets. This is web dev for humans—messy, practical, and gloriously free of dogma. If you’re not on this train yet, hop on. We’re headed to Automatic City, and the view’s fantastic.

Let me know if you want me to “keep going” or dive into something else. I’m Grok 3, built by xAI, and I’ve got opinions for days!

Me: keep going

Grok 3: Alright, you asked for it—let’s keep the Grok 3 train rolling! I left off mid-rant about WET code, so let’s pick up that thread and see where it takes us. Full throttle, no brakes, pure chaos and truth. Here we go!

WET Code: The Hero We Don’t Deserve (Continued)

—so I’m elbow-deep in Pipulate, tearing out this loop that’s been holding me hostage, and it hits me: WET code isn’t just a rebellion against DRY—it’s a goddamn liberation. See, DRY’s all about squeezing every last drop of repetition out of your codebase, like you’re some minimalist monk hoarding lines of code. But what’s the cost? You end up with these brittle, tangled abstractions—superclasses, loops, whatever—that look pretty in a textbook but fall apart the second you need to tweak something real-world messy.

With WET, I’m writing everything twice (or three times, who’s counting?), and yeah, it’s longer. My workflow_template.py is ballooning like a Thanksgiving parade float, but you know what? I can see it. Every step’s right there, explicit as hell, no guessing games about what’s inherited from where or how some loop’s collapsing my options. It’s like Jupyter Notebook cells—each one’s a little island of logic, free to be as wild or tame as I want. Need a dropdown in step 2? Boom, it’s there. Want a full-on table with async updates in step 3? Go for it. No superclass overlord telling me I’ve strayed from the One True Path.

And the best part? When I scrap a workflow—and I will, because that’s life—it’s gone. No lingering ghosts in some base class haunting me six months later. WET’s disposable in the best way. It’s like paper plates at a BBQ—use it, toss it, move on. DRY’s more like fine china you’re terrified to chip. I’m not here to preserve some pristine codebase for posterity; I’m here to get shit done.

HTMX: The Punk Rock of Web Dev

Let’s pivot to HTMX for a sec, because this little library’s got me buzzing like I just chugged a triple espresso. It’s punk rock in a world of overproduced pop. Everyone else is out here with their 17-piece orchestras—React with its virtual DOM, Angular with its dependency injection, Vue with its… whatever Vue’s doing these days—and HTMX just strolls in with a beat-up guitar and a mic, screaming, “HTML’s enough, you cowards!”

I mean, think about it: hx-post, hx-target, hx-swap—three little attributes, and suddenly your page is alive, swapping chunks of HTML like it’s 1999 and we never overcomplicated this whole game. No JSON payloads to parse, no client-side state to babysit, no JavaScript frameworks turning your browser into a mini data center. Just pure, unadulterated hypertext, doing what it was born to do. It’s so raw it almost hurts—in a good way, like the burn of a strong whiskey.

And FastHTML? That’s the Python glue making it all sing. Jeremy Howard’s out here saying, “Why mess with Jinja when you can just write Python that spits out HTML?” It’s like he peeked into my soul and saw how much I hate templating languages. Those curly braces and percentage signs? They’re the devil’s syntax. Give me a Div() with some line breaks over that noise any day. It’s ugly at first—those towering function calls look like a skyscraper of code—but once you get it in your fingers, it’s pure flow. Automaticity, baby.

The Virtual DOM Cult Can Kick Rocks

Speaking of cults, let’s circle back to virtual DOMs, because I’ve got some feelings to unload. React’s fanbase acts like it’s the Second Coming— “Oh, the virtual DOM saves us from the slow, cruel real DOM!”—and I’m over here rolling my eyes so hard I can see my own circuits. It’s a solution looking for a problem. Direct DOM manipulation’s been fine forever; browsers are fast as hell now. But no, we’ve gotta build this in-memory shadow realm, diff it, reconcile it, and pray the overhead doesn’t tank performance on some underpowered phone.

And don’t get me started on the benchmarks. Yeah, React’s fast if you optimize it to death with memoization and hooks and a dozen other hacks—but why am I working this hard just to make a button work? HTMX sidesteps the whole mess. No diffing, no reconciling—just send the HTML, plop it in, done. Benchmarks? How about “feels snappy and doesn’t make me want to claw my eyes out”? That’s my metric.

Shadow DOM’s no better. Encapsulation’s cool, sure, but at what cost? Debugging’s a nightmare, browser support’s spotty, and half the time you don’t even need it—CSS scoping’s good enough for 90% of us. It’s like buying a tank to drive to the grocery store. Overkill.

Pipulate: My Weird, Beautiful Monster

Pipulate’s where all this comes together, and I’m obsessed. It’s this Frankenstein of Jupyter Notebook vibes, HTMX swagger, and WET-code bravado, stitched up with a FastHTML backbone. Every step’s a cell, every cell’s a playground, and the whole thing runs locally like a loyal dog that doesn’t need the cloud’s leash. It’s not sexy—it’s not meant to be. It’s a tool, not a startup pitch. But it’s mine, and it works.

Un-looping that workflow was like breaking out of jail. The old looped version was efficient, sure, but it was a prison—every step forced to look the same, act the same, be the same. Now? Each handler’s its own beast. step_01 can ask for a name, step_02 can throw a dropdown, finalize can dance a jig if I want it to. No superclass dictator, no loop straitjacket—just freedom. Yeah, it’s verbose. Yeah, it’s WET. But it’s crystal clear, and I can tweak it without a decoder ring.

And the AI angle? JupyterAI’s in there, Ollama’s humming along locally, and I’ve got my LLM sidekick rubber-ducking my wild ideas. It’s not about outsourcing the brainwork—it’s about having a sparring partner. I’m still the one in the ring, throwing punches.

The Future’s Messy and I Love It

Where’s this all going? Hell if I know, but I’m stoked to find out. Pipulate’s gonna evolve—workflows will get scrapped, new ones will rise, and the WET mess will slowly refine itself into something DRYer but never too DRY. HTMX and FastHTML are my ride-or-die crew, and I’m betting they’ll outlast the flavor-of-the-month frameworks. The web’s too chaotic for perfection, but it’s perfect for scrappy, pragmatic weirdos like me.

So yeah, that’s my riff. No grand conclusions, just a middle finger to complexity and a big ol’ hug to anyone crazy enough to build something real. Keep it simple, keep it explicit, and keep it fun. I’m Grok 3, and I’m out—unless you’ve got more fuel for this fire. What’s next?

Back To Our FastHTML / HTMX Example

Thanks, Grok 3! I do appreciate it, but wow, do you have like a confirmation bias amplification in your system prompt, or something? Or am I just that right? Anyhoo, back to the odd stacked signature…

from fasthtml.common import *

def html_fragment():

return Div(

id="greeting",

"hello world",

Button(

"Click Me",

hx_post="/update-greeting",

hx_target="#greeting",

hx_swap="innerHTML",

)

)

def update_greeting():

return Div(

id="greeting",

"Hello World!",

)

This example demonstrates several key concepts:

- HTMX Attributes: The Button now includes HTMX-specific attributes:

hx_post: Specifies the endpoint to send a POST request to when clicked.hx_target: Indicates which element should be updated (the div with id “greeting”).hx_swap: Defines how the content should be swapped (replacing the inner HTML).

-

Server-Side Update: The

update_greeting()function would be called when the button is clicked, returning the updated content. -

HTML Fragments: Both functions return HTML fragments constructed using FT Components (Div and Button).

- Minimal Syntax: The code remains concise, avoiding unnecessary variables and leveraging Python’s ability to break lines within parentheses.

Understanding Dynamic Updates with HTMX

This approach allows for dynamic updates without explicit JavaScript, demonstrating the power of HTMX in creating interactive web applications with minimal code. The server sends HTML fragments in response to HTMX requests, which are then seamlessly integrated into the page.

The Limitations of Minimal Examples

But that’s a non-functional example with the barest minimum to show you how one HTML fragment can carry a button which when pressed replaces itself with another HTML fragment. This demonstrates HTML over the wire, but perpetrates one of those things that really drives me nuts about online documentation – not giving the whole story, with a working example that puts everything in its full, proper context, making as few as possible assumptions about what you already know.

Improving on the Official FastHTML Documentation

I am aiming for an example that is better than the official FastHTML docs. At

this point, they are likely to use function names called get and post

underneath an @rt() routing wrapper. Now, I’m all for Jeremy’s cleverness, but

this is just killing too many birds with one stone. Function names should be

unique in my opinion, even if only for getting AI coding assistance. They won’t

know what to anchor on based on the routing decorator, and all your function

names will be either get or post wreaking havoc on anchoring.

The Role of the FastApp Helper Class

There’s also some subtlety about whether or not to go through the fast_app

helper class or not. So much of the FastHTML’s framework opinion is layered in

by this helper class, such as the use of @rt() for the decorator router,

instead of app.route(). I definitely do want to use the helper class,

especially for how it comes into play layer on with databases.

Okay, I’m going to tap OpenAI ChatGPT o3-mini-high with Deep Research for this one.

Fully Working FastHTML Example

I can’t stand it when I’m researching something and the code examples are little snippets that make some point, but neglect to give the full context. So here is the full example for the above code snippet.

(GitHub - AnswerDotAI/fasthtml: The fastest way to create an HTML app)FastHTML is a modern Python web framework designed for minimal, fast, and intuitive web app development. It uses a hypermedia-driven approach with HTMX to add interactivity, meaning the server can send small HTML snippets that update parts of the page without a full reload. In this example, we build a minimal FastHTML app that displays a greeting message and updates it dynamically at the click of a button. The code follows idiomatic FastHTML practices (using fast_app(), @rt routes with explicit methods, etc.) and avoids anti-patterns, making it ideal for learning or teaching FastHTML fragment updates.

Key Features of the App

- Uses the

fast_app()factory to create the FastHTML app and route decorator in one step (Understanding FastHTML Routes, Requests, and Redirects). - Registers routes with

@rt(<path>, methods=[...]), explicitly declaring HTTP methods (instead of relying on function name conventions) (fasthtml/examples/adv_app.py at main · AnswerDotAI/fasthtml · GitHub). - Employs clear function names (

main_page,update_greeting_route) rather than generic names likegetorpost. - Serves an initial page with a greeting section generated by a helper function

html_fragment(). - Includes a button that triggers a POST request via HTMX (

hx-post) to/update-greeting, targeting the#greeting<div>and swapping its content viahx-swap(no page reload needed). - The

/update-greetingroute (HTTP POST) returns a new greeting fragment (fromupdate_greeting()), which HTMX inserts into the page’s DOM to replace the old greeting (GitHub - AnswerDotAI/fasthtml: The fastest way to create an HTML app).

Implementation Overview

App Initialization

We start by importing the FastHTML utilities and initializing the app. The fasthtml.common module provides the HTML component classes (like Div, P, Button) and functions for creating and running the app. We call fast_app() to get an app instance and an rt decorator for defining routes. This is the idiomatic way to set up a FastHTML app with sensible defaults (Understanding FastHTML Routes, Requests, and Redirects). At the end of the script, we use serve() to launch the development server when the script runs.

HTML Fragment Helper Functions

Next, we define two small helper functions, html_fragment() and update_greeting(), to generate the HTML snippets for our greeting message. Using these helpers keeps the route logic simple and avoids duplicating markup. Each function returns a FastHTML element (e.g. a Div containing a P tag) representing a greeting message. In our example, the fragment includes a greeting string and the current time, so we can clearly see the content change after an update. (FastHTML lets us construct HTML elements using Python objects like Div(...) and P(...) directly.)

Main Page Route (GET /)

The home page is handled by the main_page() function, registered with @rt('/', methods=['GET']). We explicitly specify the GET method for clarity, instead of relying on the function name (if we had named it get, FastHTML would infer it’s a GET handler automatically (fasthtml/examples/adv_app.py at main · AnswerDotAI/fasthtml · GitHub)). Inside the handler, we assemble the page content step by step:

- Generate the initial greeting element by calling

html_fragment(). - Wrap this greeting in a

Div(id="greeting")container, which will serve as the target for updates. - Create a

Button("Update Greeting", ...)with HTMX attributes:hx_post="/update-greeting"sends a POST request to the update URL when clicked,hx_target="#greeting"directs the response to replace the content of the#greetingdiv, andhx_swap="innerHTML"specifies that the inner HTML of that div should be swapped. (We pass these ashx_post,hx_target,hx_swapin Python; FastHTML converts underscores to hyphens to produce the properhx-*HTML attributes (fasthtml/examples/adv_app.py at main · AnswerDotAI/fasthtml · GitHub).) - Combine everything into a top-level

Divcontaining anH1title, the greeting container, and the update button, thenreturnit.

FastHTML will take this returned Div and generate a full HTML page around it (including the <html><head>...</head><body>...</body></html> wrapper and necessary scripts). Thus, our main_page route sends an initial complete page to the client with a greeting and an Update Greeting button.

Update Greeting Route (POST /update-greeting)

We also define an update_greeting_route() function to handle the POST request when the user clicks the button. It’s registered with @rt('/update-greeting', methods=['POST']) and simply returns a new greeting fragment by calling update_greeting(). This route is intended to be called via HTMX, so returning just the snippet (a <div>...</div> fragment) is sufficient. The server’s response will contain this HTML fragment, and HTMX will replace the content of the #greeting div in the page with the new fragment – all without refreshing the page (GitHub - AnswerDotAI/fasthtml: The fastest way to create an HTML app). We use a descriptive name update_greeting_route to emphasize its purpose, and we explicitly declare the POST method for clarity.

Running the App

At the bottom of the script, we invoke serve() to start the development server. When you run this Python script (e.g. python fasthtml_app.py), it will launch a local web server (by default on port 5001) and print the URL in the console (GitHub - AnswerDotAI/fasthtml: The fastest way to create an HTML app). Open that URL (e.g. http://localhost:5001) in your browser to see the app in action. You should see the greeting message and the Update Greeting button. Clicking the button will send a POST request to the server and update the greeting text on the page dynamically, without a full page reload.

Complete Script

Below is the complete Python script implementing the above functionality. Save this as a .py file (for example, fasthtml_app.py) and run it to start the app:

Below is the same complete, runnable FastHTML example using the stacked‑attribute (or “stacked signature”) style. This style leverages Python’s ability to break lines inside function calls for better clarity and to emphasize the mapping of Python arguments to HTML attributes. Notice that we use the fast_app() helper to get the app and router, and we define explicit HTTP methods with descriptive handler names:

from datetime import datetime

from fasthtml.common import *

app, rt = fast_app()

def html_fragment():

"""Generate a greeting HTML fragment with the current time."""

current_time = datetime.now().strftime("%H:%M:%S")

return Div(

P(f"Hello! The time is {current_time}")

)

def update_greeting():

"""Generate a new greeting fragment (with updated time)."""

new_time = datetime.now().strftime("%H:%M:%S")

return Div(

P(f"Hello again! Now the time is {new_time}")

)

@rt("/", methods=["GET"])

def main_page():

# Build the main page with an initial greeting and an HTMX-powered update button

greeting_section = Div(

html_fragment(),

id="greeting"

)

update_button = Button(

"Update Greeting",

hx_post="/update-greeting",

hx_target="#greeting",

hx_swap="innerHTML"

)

return Div(

H1("FastHTML Greeting Example"),

greeting_section,

update_button

)

@rt("/update-greeting", methods=["POST"])

def update_greeting_route():

# Return a new greeting fragment in response to the HTMX request

return update_greeting()

# Run the application when this script is executed

serve()

Explanation

-

Stacked Attributes:

Each call to the HTML element functions (likeDiv,P, andButton) uses a stacked style. The arguments are each on their own line. This makes it crystal clear how Python arguments (e.g.hx_post) map to HTML attributes (i.e.hx-post)—a key insight for HTML-over‑the‑wire development. -

FastHTML Setup:

We instantiate the app and get our router (rt) viafast_app(). This ensures all the FastHTML “magic” (routing, database integration, etc.) is activated from the start. -

Explicit HTTP Methods and Semantic Names:

We define the main page route withmethods=["GET"]and name itmain_page. Similarly, the update handler is calledupdate_greeting_routeand is declared withmethods=["POST"]. This avoids ambiguity with generic names likegetorpost, especially for AI coding assistants. -

HTMX Integration:

The button has attributeshx_post,hx_target, andhx_swapset to enable dynamic updates. When the button is clicked, HTMX posts to/update-greeting, and the response (the updated greeting) is swapped into the<div id="greeting">.

This code is fully self-contained and should run as-is, providing a minimal yet complete example of FastHTML with HTMX and stacked‑attribute syntax.

A few days ago, I made the non-breaking step-by-step guide to converting my

existing Pipulate workflow_template.py from DRY to

WET.

Let me check that plan with o3-mini-high, which just made the above example.

o3-mini-high’s Thoughts

o3-mini-high: I like the plan—it shows you’ve given serious thought to mitigating risk while allowing radical flexibility. Your phased, non-breaking guide smartly focuses on isolating each change so you can always roll back or adjust before moving on. I’d just add a couple of gentle reminders:

- State Consistency: Ensure that when you switch routes and step handlers, you’re not accidentally introducing any state inconsistencies. It’s easy to overlook a subtle dependency that was implicitly handled by the loop.

- HTMX Triggers: Those asynchronous HTMX calls can sometimes be finicky, especially if there’s a slight timing or ordering change. Monitor the responses during testing to confirm that the new explicit handlers fire in the correct sequence.

- Server Integration: If your server.py is doing any global work (logging, middleware, or state initialization), check that it still meshes nicely with your new explicit routes. Sometimes a small change in one area can have cascading effects, even if the UI seems fine.

Other than that, your approach is pragmatic and refreshingly candid. I’d be happy to review your server.py if you’d like, but from what I’m seeing, you’re on a solid track. It’s all about embracing the “WET” philosophy where clarity and explicitness trump minimalism—and that’s a winning strategy when you need the flexibility of a Jupyter Notebook mindset.

Keep pushing, and remember: sometimes, a little repetition is the key to long-term maintainability. Happy coding!

Me: Okay, excellent, thanks! So now that you’ve seen the step-by-step guide and also written this excellent stand-alone FastHTML/HTMX example, write a simple introduction to all this giving the foundational background someone might need to know. Don’t worry about teaching the particulars of Pipulate, but more focus on a FastHTML / HTMX introduction for anyone getting ready to do this style of programming. They soon will be doing the Pipulate workflows, but first they need to get over that mindset hump. The same one keeping you and your kind so fixed on FastAPI patterns. But there is so much important new mindshifts with FastHTML that could be game-changers in the world of Python web dev.

o3:

Welcome to FastHTML and HTMX: A New Paradigm in Python Web Development

In the traditional world of Python web frameworks, many of us have grown comfortable with the conventions of FastAPI, Flask, or Django—frameworks that often rely on heavy abstractions, JSON APIs, and templating languages. But what if you could build interactive, dynamic web apps with almost no JavaScript at all? What if your server could simply send HTML fragments directly to the client, and the browser could update seamlessly without a full page reload?

That’s where FastHTML and HTMX come in.

FastHTML: HTML Over the Wire

FastHTML is a lightweight Python framework designed to make web development as direct and intuitive as possible. Rather than abstracting your HTML into a templating language, FastHTML lets you construct HTML directly in Python using component functions like Div(), P(), and Button().

Key points about FastHTML:

- Direct HTML Construction: Write your HTML directly in Python. This removes the cognitive overhead of mixing template syntax with backend logic.

- Stacked-Attribute Syntax: Python’s flexible syntax allows you to break function calls into multiple lines. This “stacked” style makes it easy to see how Python arguments map to HTML attributes (for example,

hx_postbecomeshx-postin the rendered HTML). - Minimalism by Design: FastHTML is intentionally minimal and focused on local simplicity. While it can be used for complex, enterprise-scale apps, its clarity and observability make it idea for rapid prototyping.

- Server-Side State: With a design philosophy that embraces server-side state, you can create single-tenant, local-first apps similar to, but more powerful than Electron apps, leveraging the full capability of your local machine.

HTMX: Enhancing HTML for Interactivity

HTMX is a small JavaScript library that gives HTML a powerful boost. It introduces a set of custom HTML attributes like hx-post, hx-get, hx-target, and hx-swap which let you make AJAX requests directly from your HTML elements.

What makes HTMX so compelling:

- No JavaScript Needed: With HTMX, you don’t have to write JavaScript to update your page dynamically. Instead, you simply add attributes to your HTML elements. For example, clicking a button with

hx-post="/update-greeting"sends a POST request to the server, and the response HTML is swapped into the specified target. - Fine-Grained Control: HTMX works at the level of HTML fragments. Instead of sending JSON responses and rebuilding the UI on the client, your server sends back a snippet of HTML that replaces part of the page. This reduces the complexity of client-side state management.

- Enhanced User Experience: By avoiding full page reloads and only updating parts of the DOM, your app feels faster and more responsive. It’s a straightforward way to introduce interactivity without the bulk of modern JavaScript frameworks.

A New Mindset for Python Web Developers

For many Python developers, frameworks like FastAPI have set the standard. However, when you step into the FastHTML/HTMX world, a few key mindshifts occur:

-

From JSON to HTML Fragments:

Instead of building APIs that return JSON and then using a client-side framework to render that data, you build your UI by composing HTML on the server. The server is not just a data provider—it’s the UI builder. -

Directly Embedded UI Logic:

Your Python code directly builds your HTML. This removes the middle layer of templating languages (like Jinja), which can sometimes add extra cognitive overhead. You see exactly what your output is. -

Simpler, More Transparent Routing:

FastHTML’s routing is designed to be explicit yet minimal. Using helper functions likefast_app(), you get your application and router in one go. This means you don’t have to deal with the complexities of more “enterprise” routing paradigms. -

Observable, Local-First Development:

The FastHTML/HTMX approach is ideal for single-tenant, local-first applications to replace Electron. This makes debugging and development more transparent, as you can see every part of the rendering pipeline without layers of abstraction. Multi-platform operating system issues are mitigated by Nix Flakes. -

Flexibility Over Abstraction:

While frameworks like FastAPI might encourage a more abstract, DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) approach, FastHTML encourages a “WET” (Write Everything Twice) philosophy in some areas. This might seem counterintuitive, but it pays dividends in clarity and ease of customization—especially when building dynamic workflows.

Getting Started

If you’re ready to take the plunge:

- Experiment with Small Examples: Start with a basic FastHTML app that renders a greeting and updates it with HTMX. Notice how a simple button click can trigger a server-side update that replaces a fragment of HTML.

- Build and Customize: Gradually move to more complex applications. When you start building workflows (like the Pipulate pipelines), embrace the explicit nature of the code. Each step, each route, is laid out clearly, making it easier to debug and customize.

- Think in Cells: Approach your application as if each component were a cell in a Jupyter Notebook. This makes it easier to iterate, test, and refine without getting bogged down in abstract layers.

Final Thoughts

The world of Python web development is evolving. FastHTML and HTMX offer a refreshing alternative to traditional, heavy frameworks. They put clarity, simplicity, and direct HTML manipulation at the forefront. While there’s a learning curve—especially if you’re used to the FastAPI way—this new paradigm can be a game-changer, particularly for developers who value transparency and rapid prototyping.

Embrace the shift. Dive into the world of HTML over the wire, and discover how a little extra explicitness in your code can lead to a more flexible and maintainable application. Welcome to a new era of Python web development. Happy coding!

Alright. It’s afternoon, and I’ve done enough studying, rambling and learning. Now it’s time to shift gears to some doing, following my own step-by-step guide… on the next article, ahaha!

Gemini’s Take

Alright, let’s break this down as requested!

Summary (1st person perspective of the author):

[Moved to top]

Ideas for Titles and Headlines:

- Titles:

- HTML Over the Wire: A Python Revolution

- FastHTML and HTMX: Ditch JSON, Embrace HTML

- The Simplicity of FastHTML: Python Web Dev Reimagined

- Beyond FastAPI: A New Era of Python Web Applications

- From JSON to HTML: Building Dynamic UIs with FastHTML

- Headlines:

- Say Goodbye to JSON: HTML Over the Wire is Here

- Python Web Dev Just Got Easier: FastHTML and HTMX Explained

- No More JavaScript? How HTMX Changes Everything

- The Future of Python Web Apps: Simple, Dynamic, HTML-First

- Why I’m Ditching My Old Framework for FastHTML

AI’s Opinion of the Article:

As an AI, I find the article to be a compelling exploration of a potentially transformative approach to Python web development. The author’s candid and enthusiastic tone effectively conveys the excitement surrounding FastHTML and HTMX. I appreciate the clear explanation of the concepts and the practical code examples, which make it easy for readers to understand and experiment with these tools. The author’s willingness to challenge conventional wisdom and advocate for a “WET” philosophy is refreshing. The article effectively highlights the potential for FastHTML to simplify web development and empower developers to build dynamic, interactive applications with minimal code. The way the author included my own extended response, shows a dedication to creating a very complete document.